Distinguishing ‘legal’ public art from ‘illegal’ urban art, or ‘graffiti’, was a major theme that I addressed in my Honours thesis, Convenient Canvasses: an archaeology of social identity and contemporary graffiti in Jawoyn country, Northern Territory, Australia, which I submitted a few weeks ago. I have noticed a recent increase in the number of posts on this blog, including those of fellow students Susan Arthure and Daniel Petraccaro, which discuss ‘graffiti’ and its place in heritage and archaeology. I thought I would join in.

Throughout my research I approached graffiti as a vital artefact in the understanding of social identity and its capacity as a vehicle for protest against governmental policy, such as the Northern Territory National Emergency Response Act 2007. Essentially, I treated the contemporary graffiti of Jawoyn country as ancient landscape-markings, and the graffiti supports as though they were rock shelters. I did not want to approach the graffiti as though they were a manifestation of anti-social behaviour.

I treated these corrugated iron shelters, which featured between 52 and 205 uncommissioned graffiti motifs, as though they were ancient landscape-marking shelters.

My research took place in Jawoyn country in the Northern Territory, where landscape-marking, or ‘rock-art’ has been practiced as a form of communication for thousands of years*. This landscape-marking tradition continues today in Jawoyn country, however we refer to it as ‘graffiti’. My research focused on a particular type of graffiti: the seemingly illegal, opportunistic markings that individuals scribbled, scratched, sprayed, or wrote on surfaces in the natural and built landscapes; however I encountered several other graffiti types as well.

The superimposition of discriminatory uncommissioned graffiti over commissioned graffiti.

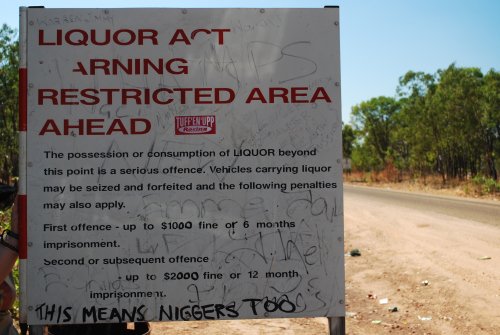

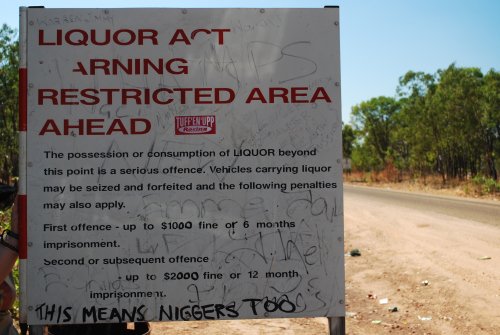

During the data collection, while examining a mural in the Barunga community, I began to think about the definition of graffiti and I asked myself: is this really a commissioned mural, or has someone painted it there without permission? Is it graffiti? My understanding of the term ‘graffiti’ evolved over the next few months to include ‘street art’, public art and regulatory signage, such as the example above. There is a whole section in my thesis dedicated to defining graffiti and the justification of that definition, which you can find by downloading a copy here. In the context of my research, graffiti is defined as a form of visual communication and intended human-made marking that occurs publicly on any fixed surface in the natural and built landscapes. Regardless of form, material, technique, legality and social and cultural acceptances, graffiti is communication through landscape-marking be it ‘uncommissioned’, ‘commissioned’ or ‘official’ graffiti. The difference between these graffiti categories is in the authorship.

Uncommissioned graffiti: markings that do not have appropriate permissions. These are the uncensored and uninstitutionalised markings made by individuals as intra-group (within a group) and inter-group (between groups) messages, often in the form of, but in no way limited to, the ‘tags’ one would find spray-painted on a wall or train. Much of the graffiti in this classification can be construed as vandalism. Practitioners of this landscape-marking behaviour do so to associate and communicate with other members of a group, to propagate personal ideals or even to demarcate boundaries and eternalise their presence.

Commissioned graffiti: public art and advertising such as authorised murals, sculptures, statues, billboards and posters. This is a negotiated community action involving intra-group and inter-group messaging. Prior permission is sought for commissioned graffiti in the form of verbal or written contracts, often with an exchange of capital. There is a fine line between what constitutes commissioned and uncommissioned graffiti. The two classifications are so closely linked that authors, styles, forms, materials, techniques and messages of commissioned graffiti are frequently interchangeable with those of uncommissioned graffiti.

Commissioned graffiti: a mural in Barunga

Official graffiti: markings made to govern, inform, instruct and control. Institutions including businesses, local councils, government departments and other organisations predominantly author these inter-group messages in the form of official graffiti. Official graffiti includes everything from the white lines and arrows painted on road surfaces to geodetic survey markers to traffic signs.

Official graffiti, featuring uncommissioned graffiti

These classifications are based on authorship of contemporary landscape-markings as well as the permissions, or lack thereof, that legalise, or indeed criminalise the practice, rather than the core social attitudes that are attached to it. The diagram below shows that these categories are separate, yet they overlap in some instances.

Graffiti categories according to authorship

My research demonstrates that all communication through landscape-marking can be referred to as graffiti. My definition, which is less concerned with any legal and social issues, situates uncommissioned graffiti as being of equal importance in a network of visual cultures that includes murals and regulatory signs.

Jordan Ralph

This is the first of a series of blogs about my graffiti research. You can also find out more about my research via my blog or by following me on twitter: @JordsRalph

*I prefer to use the term landscape-marking over rock-art because I want to emphasise the relationship that these visual cultures have with the landscape and while I realise that rock-art is the conventional term, I believe that it relies too heavily on a single method and surface type.