By Sam Hedditch- Graduate Diploma of Archaeology student.

This is the third of my four blog posts for the Flinders Cultural Heritage Practicum I am completing at the South Australian Museum stores at Hindmarsh. I am currently left with three weeks of my placement before my hours have been completed and I am a little sad because I am sure I will miss the people and the artefacts I have been lucky enough to work with.

The past few weeks have taken another exciting turn in my placement at the Museum. John Hodges very kindly included me on the work on the Koonalda Cave material from the Alexander Gallus/Richard Wright excavations. We were going through one of Gallus’ trenches to find evidence of organic materials for dating purposes within boxes that related to particular site layers. A range of organic materials (e.g. bone and shell) can now return reliable radiocarbon dates whereas previously dating was largely conducted on charcoal. We were also able to find stone tools that had ‘cementation’ of sand, dirt and limestone, as this information is part of a development in dating between geochemistry and archaeology.

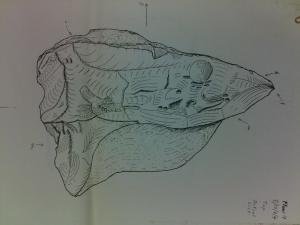

Figure 1- One of the illustrations of a Flint nodule from the Koonalda Cave. (Courtesy of South Australian Museum)

Researchers at the South Australian Museum hope to submit three small specimens from this collection from various layers in the trench to give some good preliminary dates in order to back a research grant for a more wide-scale dating program. This whole process was unfamiliar to me and the fact that many grant applications are being submitted illustrated that the best possible proposal must be put forward in order to receive the grant.

We ultimately found a range of interesting items that were suitable for C14 dating. Interestingly, we also found some small bones, possibly from a masked owl (now extinct in the Nullarbor region), that are shaped like a bone point. There was also a flint stone flake that had charcoal, bone and a cementation of limestone as its cortex, that would also be a very useful artefact for the dating program. There were also some fascinating stone flakes and what John and I thought were small picks and axes used by people in the caves to quarry the stone.

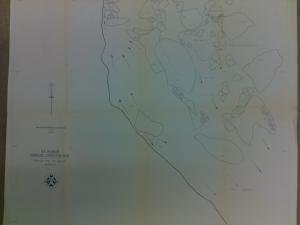

Figure 2- A dumpy level survey map of the Koonalda Cave. There are many different maps that help piece together the site and its separate excavation seasons.(Courtesy of South Australian Museum)

However, the primary goal as stated above was to find these three samples and be able to link them to various site layers in the notes and maps associated with the excavation. Dr Walshe had a number of large scale maps laid out on the work floor which had been compiled throughout the many seasons by museum staff and speleologists working in the excavations. The maps were useful in correlating all of the artefacts and the context in which they were collected.

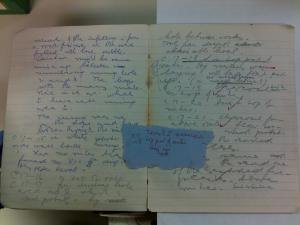

Another critical piece of evidence were the notebooks of Gallus that described the material and layers within the trench that we were sorting. Gallus’ method of recording was certainly not the easiest to follow in terms of handwriting and following a logical order re: page numbers and nomenclature etc, so we had some difficulties reconciling all of the data and finding three suitable samples.

Figure 3- A page from Gallus' notebook. This is why it is important to write clear notes! (Courtesy of the South Australian Museum)

After much time and toil, our samples were found and we are in the process of having them dated. It is again a terrific experience for me and a great opportunity to be a part of this research. It demonstrated that, due to the difficulties associated with obtaining permission to dig old sites like caves or dig new ones, there are available and complete research designs that can be implemented on old collections held in museums. Even the notes and the story of the Koonalda Cave could produce its own archaeological narrative with the right interest, care and dedication.

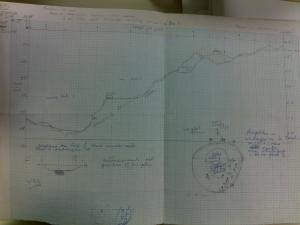

Figure 4- A profile drawn by Gallus of one of the excavation sites. This was vital information to link layer numbers on the artefacts in the boxes to the notes and the profile sketches. (Courtesy South Australian Museum)

Needless to say, museums are not at all boring places and the excitement at the Hindmarsh store is palpable. Better yet, I have three more weeks to further my own archaeological interests and work and to learn from some really humble, dedicated and inspiring professionals

Til next time!