By Danielle Wilkinson (MMA student)

Technologies are constantly evolving to assist in gathering, representing and sharing data. Photography is one area with constant developments, where new advances enable increased accuracy, simpler use, and quicker results. Artefact photography has retained basic principles over time, but there have been great advancements in its application and potential in archaeology.

Artefact photography has the potential to be a very informative and scientific resource for archaeologists. Photographs can be used as a technique for recording and to track changes the artefact has undergone over time. They also provide a way to keep a ‘back-up’ record of the artefact in case of loss or damage. Most importantly, digital photographs can be shared very easily for wide and fast dissemination. But, it is important to remember that an artefact photograph can be useless if the appropriate principles are not followed. The success or failure of a photo rests on a number of different variables, and every photograph requires considerable thought and preparation. It is not as easy as a click of a button!

Background and Lighting

Background and lighting should be re-considered before every shot as different arrangements may be necessary depending on the size and shape, material, and colour of the artefact.

The usual backgrounds used are: black velvet, which prevents shadows and reflections but cannot be used for dark objects; white (such as paper), although shadows are very visible so must be used with correct lighting; glass, used against an illuminated white surface to reduce shadows; and matte (sacking or canvass), which reduces contrast and hides shadows.

The most important aspects of lighting is to reduce the amount of shadow and highlight features. Tungsten lights are most common as they are cheap and convenient. Fluorescent lights are ideal only for black and white work due to colour distortion. Flash is vey difficult to handle, with an intense localized light that is impossible to predict. Natural light can create less shadow, especially in overcast conditions, but again is limited to black and white due to colour distortion. As you can see, lighting and background arrangements can depend on each other, and vary depending on the artefact.

Scale and Identification

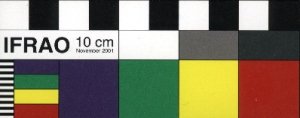

IFRAO Scale (Image: http://mc2.vicnet.net.au/home/record/web/scale.html)

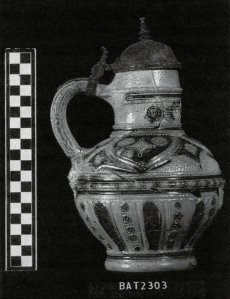

Usually a one-centimetre scale is used. When the photograph is taken, the widest plane of the artefact will be seen in profile view. If the scale is not level with this plane then the measurements of the scale to the artefact will be distorted. Hence, the scale should be raised to coincide with the outline of the object. It may be necessary to use multiple scales if a specific feature is also being photographed, or multiple photos should be taken. The scale should be placed near the frame of the photo without touching the artefact, so that it can be cropped out later on. Identification is handled with the inclusion of the artefact registration number tag, which is also placed near the frame.

Westerwald ware jug from the Batavia – notice scale placed in plane of outline, identification tag near frame, and black background to contrast (Image: Green (2004) Figure 12.5)

Camera

Advances from the ‘old school’ conventional cameras are phenomenal. Digital cameras are becoming cheaper and much easier to use. Instant review on LCD screens allow the photographer to adjust settings and re-take photographs, and saving onto a memory card enables easy transfer to a computer. Computer software is another major development, essentially making a ‘digital darkroom’ where the photo can be adjusted in a number of ways.

Without getting technical, there are basics that any archaeologist should be aware of. The first is that there are different kinds of cameras and lenses that are appropriate for different shots. The camera most commonly used in archaeology is the 35mm, single-lens reflex (SLR) camera with interchangeable lenses. Lenses range in angle, length and zoom, but the most useful for artefact photography is a general purpose 35-105mm macro zoom lens, which can also be used in expedition photography, as well as the Macro telephoto of 100 or 200mm focal length, for accurate and detailed object photographs.

Nikon 35mm SLR Camera (Image: http://www.bhphotovideo.com/c/product/597062-DEMO/Nikon_F75_35mm_SLR_Autofocus.html)

Aperture, Shutter Speed and Focus

Aperture and shutter speed settings may be unfamiliar to anyone new to artefact photography (they certainly were for me!). Aperture, or f-stop, controls the ‘depth of field’ – how much depth remains in focus. This is done by altering the size of the hole controlling the amount of light passing through the lens. The depth in focus is increased by reducing the f-stop number (if it helps, imagine the diameter as a fraction with the diameter divided by the f-stop number [d/f] i.e. ½ for a larger hole and larger depth, or ¼ for a smaller hole and smaller depth). This setting is important when photographing an object with a varying depth, as the whole artefact should be kept in focus. Shutter speed has a combined effect as it controls the length of time that the chip (or, originally film) is exposed to light, controlling the darkness of the picture. If the aperture is adjusted, the lightness of the photograph will be affected, hence the shutter speed also needs adjusting.

Lastly is the focus. When adjusting focus, it is important to watch the detail and profile. The outline of the artefact should appear sharp, as if the object is hovering. Focus is not something to be done quickly, and it may take some adjusting of the f-stop to get it right. Always review the photograph and check the focus before moving on. It could also be suggested to take multiple photos at different f-stops and shutter-speeds so that they can be compared.

Saving

All archaeologists know that it is important to catalogue and store data correctly and in an efficient manner, and it is no different with photographs. The photos should be labeled with the registration number of the artefact, and with any other necessary details such as the site name and date. A computer database is the best system for storing, but photos should at least be saved on a disk or external hard drive, which are economical and can be very large – in fact, most students I know own a hard drive of at least one terabyte, just for movies and music!

Artefact photography has a large potential for the sharing of information. With new technologies, it is becoming an easier, quicker, and more accurate method for recording and as a resource. With more accurate photographs there is less of a need to handle the actual artefacts, and archaeologists far removed from its location are not disadvantaged or restricted by access. Future developments are difficult to predict – perhaps three-dimensional technology will become more accessible, and 3D images will be taken of artefacts to recreate their complete shape. What about projected holograms? For now, archaeologists should take advantage of photography and use it to their advantage. It is simple to learn and, as long as you follow the principles, anyone can do artefact photography.

References:

Green, J. “Artefact Photography” in (2004) Maritime Archaeology: A Technical Handbook. 2nd Edition, pp.325-345.

Dorrell, P. G. “Principles of Object Photography” in (1994) Photography in archaeology and conservation. 2nd Edition, pp.254-176.

Bowens, A. (ed.) “Photography” in (2008) Underwater Archaeology: The NAS Guide to Principles and Practice. 2nd Edition, Wiley–Blackwell, London, pp.71-82.