Jane Mitchell

Significance adj. the quality of being significant or having a meaning

(The Macquarie Dictionary 3rd edition)

The project I’m working on aims to evaluate current statements of significance for those Victorian shipwrecks that have associated artefacts collected by Heritage Victoria.

The Heritage department is about to embark on an assessment of the significance of its shipwreck artefact collection. In light of that, it is especially important the shipwrecks the artefacts came from have sound statements of significance to provide a framework for the assessment of the collection.

The significance of particular items of cultural heritage will mean different things to different people … and over time what is considered important can also change. A thorough significance assessment is critical in properly understanding the meaning and value behind an item and is the foundation on which all management plans should be built.

Maarleveld et al. sum up the problem nicely: like beauty, significance cannot be defined in legal terms (2013: 83). However, any subjective opinion must be removed as much as possible. Therefore, methods for assessing significance have been developed for use by managers responsible for items of cultural heritage.

Assessing Significance

There are various methodologies for assessing significance but all have the same central process:

- Research the history of the wreck including its history since sinking.

- Compare and assess against a defined set of criteria.

- Write a statement that distills the essence of a wreck’s significance into a sound bite that encapsulates as much as possible.

The cornerstone of Australian heritage practice is the Burra Charter (the Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance) first adopted in 1979. Government legislators and funding bodies give preference to work that follows the processes and approach of the Burra Charter (Marquis-Kyle & Walker 2004:6).

The cornerstone of Australian heritage practice is the Burra Charter (the Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance) first adopted in 1979. Government legislators and funding bodies give preference to work that follows the processes and approach of the Burra Charter (Marquis-Kyle & Walker 2004:6).

The charter uses five values to define cultural significance: aesthetic, historic, scientific, social and spiritual. These criteria are always listed alphabetically and one is not considered more significant than another.

The Australian Institute of Maritime Archaeology’s (AIMA) Guidelines for the  Management of Australia’s Shipwrecks (1994) is the only Australian publication that deals specifically with assessing significance for shipwrecks and uses eight criteria to do so:

Management of Australia’s Shipwrecks (1994) is the only Australian publication that deals specifically with assessing significance for shipwrecks and uses eight criteria to do so:

- Historic

- Technical

- Social

- Archaeological

- Scientific

- Interpretative

- Rare

- Representative

The last two criteria are considered comparative and allow the significance of a wreck to be placed into a broader context, thereby fixing its place into the wider cultural landscape.

Reference must also be made to the Guidelines for Investigating Historical Archaeological Artefacts and Sites, published by the Heritage Council of Victoria in December 2012. The Council has updated its eight criteria, which are different to, but encompass the same ideas as, the AIMA criteria.

It should be noted that, whatever criteria are used, not all of them must be met for a wreck to be deemed significant. It should also be remembered that significance could change over time and as such needs to be revisited and revised regularly.

The Victorian scene

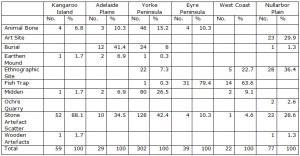

All information relating to shipwrecks in Victoria are registered in the Victorian Wreck register. The register contains fields for the physical attributes and locations of a wreck and allows uploading of any images, surveys and management plans. There is also a field for Statement of Significance. A quick database search of all shipwrecks reveals that, out of 705 registered shipwrecks, 252 have been located and of those, just under half have significance statements attached to them.

All wrecks on the Victorian Heritage Register with or without a Statement of Significance

In Victoria, either the Commonwealth Historic Shipwrecks Act (1976) or the state Heritage Act (1995) provides protection to shipwrecks. These pieces of legislation give blanket protection to all shipwrecks and relics that are 75 years and older – whether their location or existence is known or not. This implies an inherent level of significance to a wreck or relic without the requirement to demonstrate it.

Wrecks 75 years or older with or without Significance Statements

Project scope

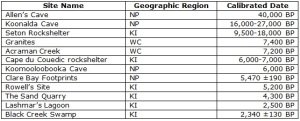

My Directed Study project is starting with an assessment of 18 shipwrecks that Heritage Victoria has been involved in excavating and/or has collected artefacts from. These include well-known wrecks such as Loch Ard and SS City of Launceston and other lesser known ones such as Foig-a-Ballagh. There is even one existing under reclaimed land: HMVS Lonsdale.

The 18 wrecks of this assessment project. Note: EMu is the collections database and numbers indicate the number of artefacts held in the collection for each wreck.

A quick review of the information in the database for these 18 wrecks has revealed that 15 have Statements of Significance. So now we know the quantity, what about the quality?

The statements of significance range from a short paragraph to one sentence. Compare Loch Ard:

The Loch Ard is historically significant as one of Victoria and Australia’s worst shipwreck tragedies. It is archaeologically significant for its remains of a large international passenger and cargo ship. It is highly educationally and recreationally significant as one of Victoria’s most spectacular diving sites, and popular tourist sites in Port Campbell National Park.

To HMVS Lonsdale:

HMVS Lonsdale is historically significant as a relic of Victoria’s colonial navy.

There is no breakdown of the assessment criteria for any of these wrecks in the database. While this information may be in conservation or management plans, these are not necessarily uploaded into the database. There is also no date so it is impossible to ascertain when the statement was written.

As I’ve searched through the database and researched the nature of significance I am struck by the thought that this lack of detailed information has been created in part by the very pieces of legislation designed to protect the wrecks themselves.

Blanket protection, which assumes a level of significance of all protected wrecks, does not require significance assessments for a wreck to be entered in the register. Currently, wrecks are being protected based solely on age, as others that may have more significance are decaying. However, as resources are limited in the current economic climate, priorities need to be in put in place. Significance assessments are an important part of that process.

In most cases, shipwrecks are intangibly tangible relics from the past. They exist out of sight under the water and are visited by relatively few. Underwater cultural heritage managers need to provide solid significance assessments, that are readily available and easily accessible. Only then will we be able to put forward a credible case for sufficient funding to preserve our shipwreck heritage. Hopefully this project will be a start to that process.

You can read about how I used the criteria to write a statement of significance for HMVS Lonsdale here.

What are your thoughts on assessing significance of shipwrecks? How do they differ from terrestrial sites? I’d be really interested in your opinion.

References

Australia ICOMOS 1999 The Burra Charter: The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance.

Australian Institute for Maritime Archaeology. Special Projects Advisory Committee & Australian Cultural Development Office & Australian Institute for Maritime Archaeology 1994 Guidelines for the Management of Australia’s Shipwrecks, Australian Institute for Maritime Archaeology and the Australian Cultural Development Office, Canberra.

Marquis-Kyle, P. & M. Walker 2004 The Illustrated Burra Charter. Good Practice for Heritage Places. Australia ICOMOS.

Maarleveld, T.J, U. Guerin and B. Egger (eds) 2013 Manual for Activities Directed at Underwater Cultural Heritage. Guidelines to the Annex of the UNESCO 2001 Convention. UNESCO Paris.

The cornerstone of Australian heritage practice is the Burra Charter (the Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance) first adopted in 1979. Government legislators and funding bodies give preference to work that follows the processes and approach of the Burra Charter (Marquis-Kyle & Walker 2004:6).

The cornerstone of Australian heritage practice is the Burra Charter (the Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance) first adopted in 1979. Government legislators and funding bodies give preference to work that follows the processes and approach of the Burra Charter (Marquis-Kyle & Walker 2004:6). Management of Australia’s Shipwrecks (1994) is the only Australian publication that deals specifically with assessing significance for shipwrecks and uses eight criteria to do so:

Management of Australia’s Shipwrecks (1994) is the only Australian publication that deals specifically with assessing significance for shipwrecks and uses eight criteria to do so: